The Life of

Lyle Walter Conzett

1898-1980

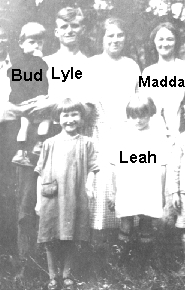

Lyle W. Conzett was born August 14, 1898 in Dubuque, Iowa. He was the third of 13 children born to Walter Eugene Conzett and Kathryn Marie Albert. Theirs was a working class family living on the western side of Dubuque's downtown, rooted in the growth years before the depression, and the wonder of the post-Victorian era. Walter was a strong, resilient stonemason, whose finely crafted stones can still be seen in many of the buildings of Dubuque today, Kathryn was the daughter of a Civil War veteran, strong willed and even tempered. Long lived, Walter lived to age 85, passing away in 1962, while Kathryn survived to a spry age of 97, passing on in 1976.

Lyle was slender, almost wiry in build. His height was average, his hair fair, and his eyes blue. Lyle maintained an almost boyish appearance even into his late teens and early 20's. Quick with a smile and a friendly hand, he was an instant friend to all he met. His personable manner was charming and true. Lyle was never immune to hard work; he sought the challenge of the job, and the satisfaction of its proper completion. These strengths were a hallmark throughout his life, as one who could be depended upon with reliable results. This wonderful dependability will always shape my memories of "Grampy".

Lyle was just 18 when he married his sweetheart on May 8,1917: Anna Magdelena Osterberger. Madda (May-da), as family and friends knew her, was a pretty, petite bride with a glowing smile. They were to have three children: Leah Catherine, born November 30, 1917, Lyle August, born March 8, 1922 and Sandra Jeanne, born January 28, 1942. As a family, they were fond of drives into the country, fishing on the Mississippi and in the small lakes and streams of Iowa's backcountry, picnicking at the Old Shot Tower and other outdoor activities. Madda was always in the navigator's seat, as they made their way down the paths known then as roads. Lyle was especially fond of hunting.

On January 26, 1942, Madda gave birth to their daughter Sandra Jeanne. Madda had had a series of miscarriages and was told by her doctor that another pregnancy may cause severe complications. When Sandra was born, premature and sickly, the doctors held as grim an outlook for her survival as they held for Madda. Madda died of complications on January 28, and Sandra followed on February 10. Mother and daughter now rest together for eternity in a shared plot in Linwood Cemetery, Dubuque.

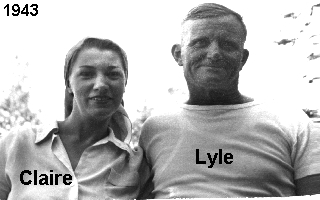

During their 24 years of marriage, Lyle and Madda had always maintained a close relationship with Madda's large family. During the period of intense grief that followed her death, the Osterbergers showed exceptional kindness and caring to Lyle. Lyle became a focus of compassion for Claire Estelle, Madda's younger sister, eventually blossoming into love and devotion. They were married in February of 1943. A match, perhaps, made in heaven.

Lyle had always lived in apartments or flats. In the early 1960's, he and Claire took the plunge and bought a house on Green Street in Dubuque. Over one hundred people attended the housewarming party. An open, airy home, they lived there until after Lyle's death on November 27, 1980 from complications of cancer. As his medical needs increased, Lyle entered residence at Luther Manor, a Methodist retirement home in Dubuque. His was a slow passing, allowing him to taste life once more before death. He now rests in Linwood Cemetery. Claire resides in her own apartment at Luther Manor today, having sold the home she shared with her beloved husband to her brother, Jake Osterberger, to fund her permanent apartment. Today at 86, she is slowing down a bit. Nevertheless, "Waree" maintains a standard of grace, poise, dignity and intellect which is unmatched by any I have known. It is apparent why Grampy fell in love with her.

A Career With The Telephone Company

With so many brothers and sisters to feed, Lyle was forced to leave school after the eighth grade to help feed and clothe his family. Lyle's love of the outdoors was perfectly suited for his chosen career paths.

In 1913, at age 15, he took his first full time job as a wagon driver for Moser's Laundry. He held a special fondness for the old man known to all the community as "Grandpa Moser". I wonder if he realized that this man was Frederick Moser, brother to his grandmother: Katherine Moser Conzett. He worked there for about a year.

Next, he worked for Mr. Jenni, the proprietor of a grocery store catering to the elite of Dubuque. Lyle delivered the groceries, driving a wagon pulled by Roy, a beautiful chestnut brown bay horse. He took extra pride in polishing Roy's brass harness with the contents of the big bottles of Blue Ribbon Paste and in grooming Roy. "I was proud of both Roy and the harness, and nothing gave me greater pleasure than to have both of them shiny and trim," Lyle once wrote.

In the fall of 1916, Lyle was hired as an Apprentice Installer of inside cabling by the local Iowa Telephone Company for $17 a week. This was his bid for independence and stability in his quest for marriage. In the summer of 1918, the local Iowa Telephone Company was absorbed into the Bell Telephone System.

Many of Lyle's fondest memories were of working the "toll lines" of the area: maintaining, building and repairing the vital long distance telephone links to surrounding cities. During his career, his work title was primarily that of a Toll Patrol Lineman. Toll lines were the long distance cable routes between cities. Patrol linemen would maintain these lines’ integrity against nature and mechanical failure.

One of his jobs was to clear trees and brush along a right of way for the lines to be installed. All vegetation would be cut down in the right of way, except for a single tree in the middle of the right of way every 100 feet or so. That tree was denuded of all its branches, and line hardware was attached by hand drilling the trunk at about the 25-foot level with a brace and bit. After the hardware was in place for as much as a mile of new right of way, the cable would be laid at the base of the tree/poles for as long as the reel would stretch. A wagon team hauling the cable reel usually accomplished this. Once reeled out, the linemen would raise the cable into place and clip it in place on the insulators. This was very hard and, quite often, dangerous work.

It was not unheard of for linemen of the day to lose fingers from cables snapping under tension and whipping. Lightning was a frightening hazard from miles away. Bees, hornets and wasps were an everyday problem. Nevertheless, stoically, the linemen went about their jobs every day of the year. When ice or snow took down lines, or when a tornado or wind storm blew down the lines, these early linemen were on site by whatever means they could to restore service: by foot, team, bob-sled, boat or horse. It was a matter of pride and professionalism that they would restore the lines as quickly as possible, and often with great challenge.

When World War I came, Lyle was drafted. Because his work with the telephone company served a vital national defense interest, he was turned away. World War II came and he was eager to do what he could to help defend his country, and to escape the grief and memories of losing his beloved wife and daughter. Lyle was drafted in the fall of 1942 at the age of 44. After being poked, prodded, examined and tested, he was rejected because the War Department reduced the maximum age of enlistees as he was being classified in Des Moines. He returned to Dubuque and resumed his duties with the Phone Company.

Lyle recalled a winter day when he and another lineman set out to clear trouble on the Waterloo-Dubuque toll line. The temperature was below zero, the snow falling in near blizzard conditions. After clearing the trouble, they lost their way back to their truck. They walked in hip deep snow with tools and materials searching for the truck. They found it near 11 o’clock that night, and finally made it back home to the relief of all who were searching for them. In 1955, the dangers of the job would finally catch up with him.

Linemen of yesterday and today use a spiked brace apparatus on their feet known as gaffs, spurs, hooks or climbers. These steel braces curl beneath the shoe instep and extend up the inner calf, with strong leather straps affixing them tightly to the legs. A steel spike, or gaff, extends downwards about 2-3 inches from the instep of each climber. A lineman climbs a pole by grasping the pole on either side with his hands and plunging the gaff into the wood of the pole. As he climbs, he steps up the pole by alternating sides, stepping down on the gaff and seating it deep into the wood on either side of the pole. Once up to the working height required, a lineman will deeply seat his hooks into the pole, wrap his safety belt around the pole and lean back against the belt. This leaves his hands free to work on the line hardware.

A properly trained and experienced lineman never uses his safety belt while climbing or descending a pole. This is due to the dangers of "cutting out". Should the gaff point hit a knot or nail, if the pole is "green" or very hard, or simply the angle at which the gaff point is inserted into the pole not be acute enough, the gaff tip can break out of the wood's surface and slide down the face of the pole. If the gaff on the other leg is not firmly planted in wood, the lineman will begin to fall. If his safety belt is around the pole, the lineman will "burn" the pole: sliding to the ground with his hands, face, belly, crotch and legs scraping and bumping down the pole. Any lineman will agree that it is better to have to deal with a broken leg than to have to deal with a broken leg AND pull splinters out of your body for a month and be scarred for life. Today's poles are worse, covered with creosote that burns like sin in a cut or splinter. Therefore, linemen do not use their belts when climbing or descending so that if their gaffs do cut out, they can push away from the pole and (hopefully) land safely in the grass.

This is the reason public utilities request that signs not be placed on utility poles for garage sales and the like. The nails or staples can cause a repairman's gaffs to cut out, or inflict terrible injuries to him if he should burn the pole.

Lyle's gaffs cut out while descending a "black diamond" pole in 1955. He pushed off, but fell at the base, severely hurting his back. After surgery for a herniated disc in 1956 (a result of the fall the previous year), the company's doctor told him he could no longer climb poles or perform lineman's duties. He was assigned to the warehouse as a storekeeper for the balance of his career. He mourned the loss of his outside lineman's duties, and was never happy with his new job. Lyle retired in 1963 with over 45 years of service to Northwestern Bell Telephone, as it was known then.

A Hero In More Ways Than One

Along the way, Lyle distinguished himself with more than one heroic lifesaving act. In 1927, three women riding in an automobile were almost killed when their car overturned in front of him as he drove to Cascade, Iowa inspecting the toll lines. The auto’s steering knuckle broke, causing the car to swerve into an embankment. Two of the women's heads were bleeding severely after they were thrown through the windshield (this was long before the days of safety glass). Lyle performed emergency first aid on both, then climbed a nearby pole and called for an ambulance and doctor using his lineman's test set. All three women survived, due only to his actions.

On a hot June evening in 1942, a young boy walking home from a local store tripped and fell on his newly purchased bottles of milk in front of the Conzett home, severely cutting his left forearm. Lyle again performed lifesaving first aid, applied a tourniquet with his daughter Leah’s help, and carried the boy and his mother to a doctor. The mother later remarked that the boy could have died from blood loss had Lyle not taken the actions he did so quickly and correctly.

Another very frightening incident occurred, one involving Lyle’s own son. The toll linemen were working toll lines southwest of Dubuque on a summer day about 1932, repairing and cleaning the relays that needed so much attention back then. All of the residents of the areas he worked in knew and liked Lyle. Every day a family would invite him in to lunch, for water or coffee, to warm up or cool down. One particular family invited Lyle in for lunch along the stretch of lines he was working. He gladly accepted. The next day, Lyle brought his son Lyle A. (Bud) to work with him. The same family again invited them to lunch, and again he accepted. As they neared an outdoor well near the family's house so that they could wash before eating, a large dog ran past Lyle and attacked Bud. Bud ducked as the dog jumped at him, and the dog sunk his teeth into the boy's scalp. As the adults beat and wrestled the dog off Bud, the dog very nearly tore Bud's scalp off his head. Once freed from the dog's grip, it was apparent the seriousness of the attack. Lyle bundled up his boy and rushed him off to the nearest hospital, bleeding profusely. They re-attached his torn scalp, and he was to wear a turban bandage on his head for the rest of the summer. Bud was frightened of large dogs for many years after that, and he bore the scars of the attack near his hairline for the rest of his life. Lyle never again brought his son to work with him.

Lyle was a good Methodist, a Mason for over 50 years, a member of the Telephone Pioneers of America, a fixture of the community for the entire Dubuque area, a loving husband and devoted father and grandfather. He modestly acknowledged the citations he earned for saving the lives of others, but that same modesty required him to say that anyone would have done the same thing, given the opportunity. I say others may have performed the same actions, but none would have been more caring or compassionate. That level of dedication to duty, loyalty to family and friends and dependable devotion is rarely seen today. His love of family and commitment to service is a rare commodity, one that will be missed by all that knew him, and hopefully, an inspirational quality affecting all who read this tribute.

May God bless Lyle Walter Conzett, and may he rest in peace.

Sources:

Lyle Walter Conzett; personal papers; essays written for entry in Northwestern Bell Telephone newsletter outlining history of the company and its workers;

Claire Estelle Osterberger Conzett (widow); personal interviews, handwritten notes, compiled journal entries and narratives and letters assembled over a lifetime;

Leah Catherine Conzett Blair (daughter); personal interviews and handwritten notes and letters;

Barbara Jeanne Blair (granddaughter); personal interviews; compiled notes and papers written in school;

Dubuque Telegraph/Herald newspaper;

Northwestern Bell Telephone; internal papers; company newsletters; retirement papers;

Telephone Pioneers of America, Hawkeye Chapter 17; newsletters; retirement papers.